We are the problem

The untold affordability story

Photo by Jezael Melgoza on Unsplash

Hello,

Welcome to Known Unknowns, a newsletter that thinks it’s great we are getting richer.

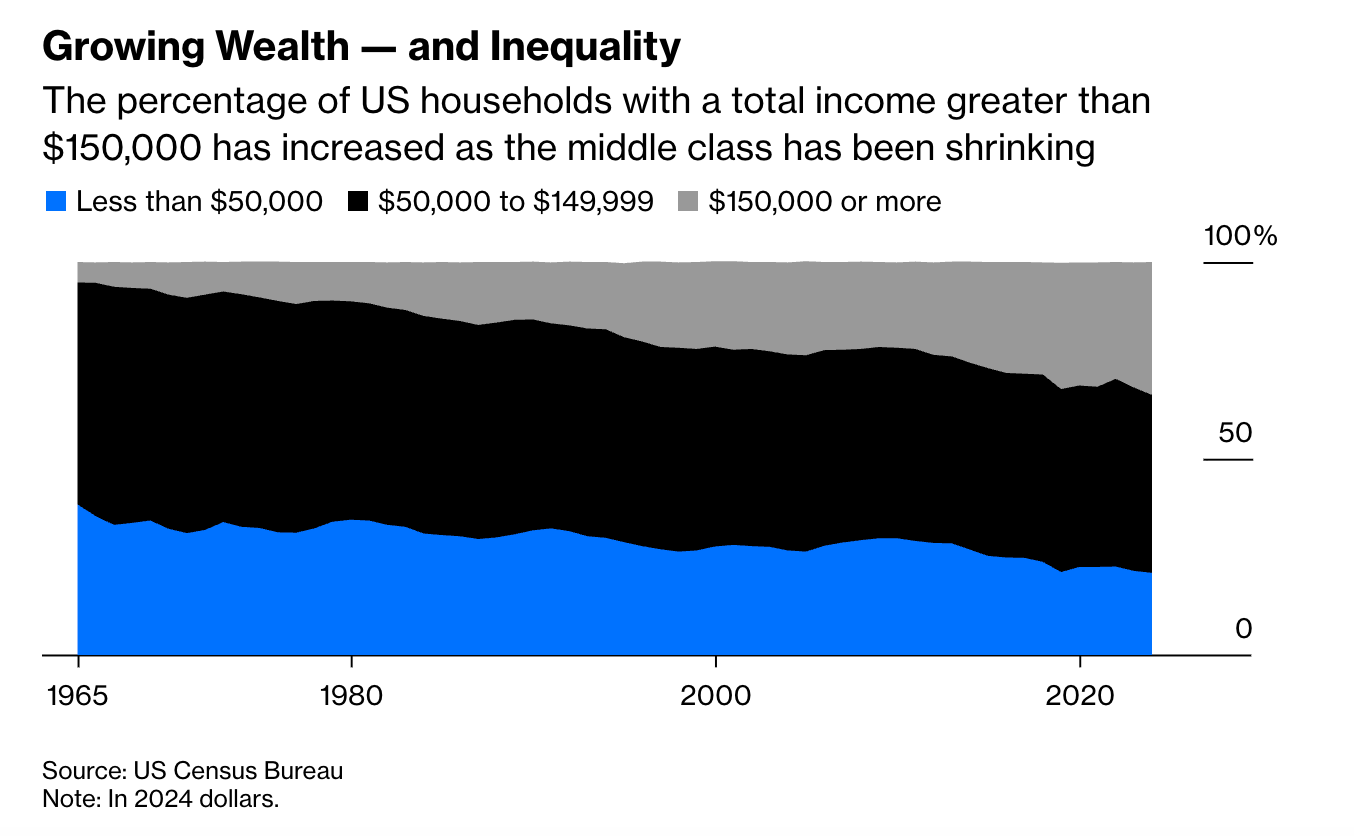

Blame the upper middle class

I have a new theory about affordability. On the one hand, it is a mystery: real incomes are up for every income group, but people feel they can’t keep up. I am starting to think the problem is that things are out of equilibrium. In the last few decades we’ve seen a shift in the income distribution. It’s true the middle class has been hollowed out, but not because people got poor or billionaires got richer, or whatever is the negative, zero-sum story of the day. Nope, markets worked, more people joined the ranks of the upper middle class; the distribution flattened and moved right. Some people got super rich, but many more got a little rich. The problem is we have an economy still built for a world where we have a big middle class, or a bell-curve income distribution.

I thought of this reading some new research about why housing is so expensive. Yes, I know we are supposed to chant three times “we need to build more housing!” every time this is brought up. And yes, we need more housing. But I am always skeptical of mono-causal explanations for any big problem. Additional research estimates part of the problem is that so many people got richer. Rising home prices are correlated with rising income. This is why, while housing is more expensive, it is also much bigger and nicer. It is also why if you are young and/or just truly middle class you are priced out of the market. And even if you are affluent there is more competition for not-great options.

You can tell the same story for concert tickets. There is a market for people who will take their daughters to see Taylor Swift for $1,000 each, it’s not the algorithm’s fault. Like many periods of disequilibrium, I reckon it will work itself out. Prices adjust, expectations change, or the market finds a way to come up with more supply.

The risk is we are now blaming billionaires for affordability, or just think they should pay for things. They are not the problem, we are. But instead of fixing the problem or letting markets adjust we have price controls, antitrust, punitive taxes, and industrial policy. This will make the problem worse and keep the market from adjusting as it should.

Japan Is a warning

If there is one thing we know for sure, it is that people can suddenly become collectively ignorant. Like in the 2010s when everyone decided 0 rates would be a thing for the rest of our lives no matter what policies we pursued. Japan became the example: “look at their 200% debt-to-GDP ratio and their rates are low! We can do it too!”

I am not sure why a slow-growing economy was what we aspired to then or now. But in any case, there were things about Japan that made it different. Besides, their financial repression model fell apart once inflation returned worldwide. Suddenly Japan had to increase rates or live with inflation—and inflation kicks off a vicious cycle of depreciation, even higher inflation, and even higher rates.

Take this as a warning: just because a financial condition holds for 10 years does not mean it will last forever. If you held Japan up as an example that rates don’t increase when you run lots of debt, you need to now use it as a cautionary tale that debt matters.

In times of uncertainty turn to finance 101

These are wild times for markets. How about that volatility in the stock market, what’s going on with gold, or the crypto winter? Is AI a bubble or the second coming, or both?

There is a way to explain it all: the basics from finance 101. It turns out bond prices mean revert. Diversification is your best bet, including owning foreign stocks. As iffy as it looks now, Treasuries probably are your risk-free asset because risk free means zero (or negative) correlation with the market.

Diversify and then hedge with something low or no risk, and that’s all you can do. Turns out all that still holds. Gold is not risk free, and the whole crypto thing never made sense. If you are into it, no judgment, but also no guarantees.

I think people don’t appreciate what we know about finance is based on many years of data. The last 10 years does not negate everything we’ve ever known.

Some exciting news!

I finally have the publication date of my next book, September 22! It is about our changing relationship with risk: how we define it, avoid it, and manage it. We are becoming more risk averse in many ways while the world becomes less risky. In theory there is nothing wrong with that, but it is expensive and means we all get less. Lots of ideas I’ve been exploring here. More on that in the coming months!

Until next time, Pension Geeks!

Allison

I have been thinking a lot about affordability, without coming to a convincing answer. But I believe that every income or wealth group suffers from their own, specific affordability concerns. The poorest part of the population has true affordability issues, i.e., with rent, food, transportation etc. But the middle class and even the uppermost middleclass is suffering from unattainability syndrome. The lifestyle which they observe on social media, TV, or read about, requires much more money than they have, but they feel somewhat entitled to it. People remember a seemingly easier past when luxury hotels cost $300, great cars sold for 50k, and business class tickets were 2k. Even I fondly remember going on a packaged one week ski trip to Aspen for 4k - for two people, including flights, in 2004. The luxury segment has become ridiculous, but that's the world that everybody wants to be a part of. Luxury price inflation...

The people I know that are struggling, never learned to, or refuse to follow, one simple action. Delay gratification. The Chinese say ''bide your time and hide your capabilities." True.