The problem of abundance

Not a bad problem to have

Photo by Bas van den Eijkhof on Unsplash

Hello,

Welcome to Known Unknowns, a newsletter where my entire conception of value may no longer be valid—but I’m still hanging on.

The crisis of abundance

These are crazy times, full of chaos and upheaval. For me, there has always been one place that helps me make sense of it all and cut through the noise: the market. It takes people with different preferences, budgets, time horizons—whatever—and distills all that into a single price for goods and services. Trade happens. People are better off. It’s pretty incredible.

But markets face a tough challenge these days because we’re dealing with a crisis of abundance. And no, I’m not making an “abundance bro” argument. The issue is almost the opposite: we have an abundance of nearly everything—except housing.

Take diamonds. They have special meaning to me—not only as a lover of jewelry, but as an economist. The paradox of value, why diamonds are worth more than water, is foundational to how we think about why anything is worth anything. Scarcity is a big part of value. But with cheaper lab-grown alternatives, diamonds are no longer scarce. And it’s not just diamonds—music, intellect, and luxury handbags are more abundant than ever.

I wrote for Bloomberg about how Hermès has managed to create artificial scarcity with the Birkin bag. I think a lot about the handbag market—not just out of professional interest as an economist. For some reason, social media bombards me with videos of people buying Hermès bags on the primary market or selling them on the secondary market. I’m not sure why, but it’s fascinating. The spread is interesting, but so is everything about these markets. And to make it even more interesting, there are tons of fakes—some of them very good. They’re still leather handbags, for a fraction of the price. Yet people still pay $10k to $35k for the real thing, and wait years for the privilege—because the real ones are rationed. Plus, the secondary market only values the real thing. Kind of like diamonds.

Is this the future for all now-abundant goods? It doesn’t work for everything—we can’t ration our labor this way, and even diamonds require a bigger market. This crisis of abundance isn’t necessarily bad—more is good. But it will upend markets and our notion of value in the meantime.

I suspect we’ll end up with segmentation. High-quality authenticity will matter and appeal to high-income buyers. Food was once scarce but is now super-abundant: you can get potato chips or a gourmet meal. Soon you’ll be able to use AI for good-but-“meh” insights, and you’ll still have to pay up for a Nobel laureate. And the market for small, imperfect natural diamonds might vanish altogether.

The Hesession

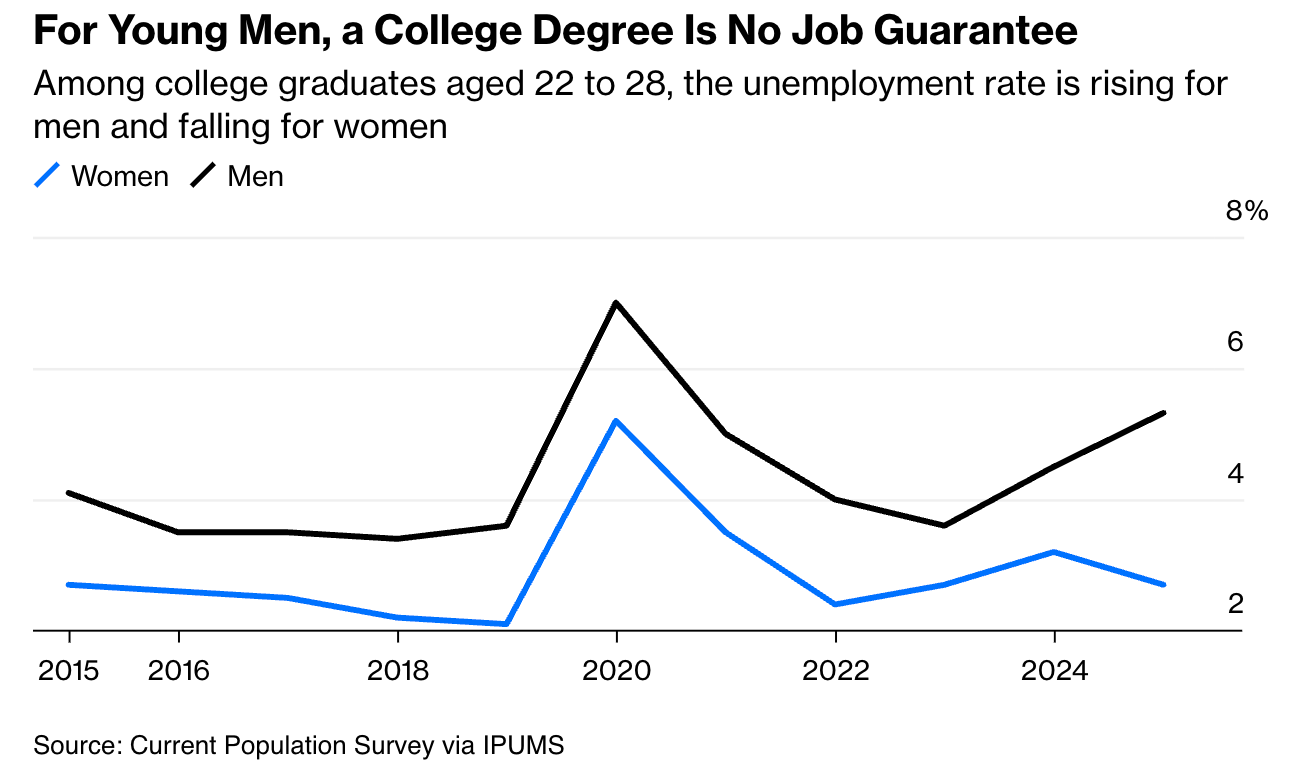

Is it just me, or have we been in this vibe-session for three years now? We keep saying the economy is terrible, yet all the economic indicators scream, “everything is fine.” In part, that’s because prices are higher, and inflation is quite harmful. There’s also an important corner of the labor market that is struggling: young men—even college-educated men, even men with economics PhDs!

Young men always bear the brunt of a slowing economy more than everyone else. They work in jobs that are more sensitive to the business cycle, and young workers tend to be the first fired or not hired at all. But something odd is going on, unemployment is still low in traditional male industries, like construction and manufacturing. It may not just be a blip in the cycle or a weak economy.

Instead, it may be a structural change that demands less skilled male labor. And if so, we’re going to have all sorts of problems that impact everyone. The question is, how do we deal with an abundant labor supply that still requires re-skilling?

Market concentration

Abundance has created another odd side effect—market concentration. In a world where scale matters, bigger companies have a natural advantage, and that’s one reason we have more market concentration—which upsets people on both the right and left.

To the extent that markets change and so does their optimal structure, I’m not too upset. But I am upset by artificial barriers that make it harder for small businesses to operate. Take the recent zeal for rent control (why we need to retry our failed economic policies, I don’t know, the outcome never changes). It gives bigger corporate landlords a big advantage because they can diversify across market-rate units or just places that have more sane housing policies. We have many such policies that penalize small businesses, mainly coming from politicians who claim they hate corporate power.

What did they expect would happen?

Until next time, Pension Geeks!

Allison

The problem of abundance is entitlement.

Would love you to discuss economic outcomes with the President of the Teamsters. Seems very Hobbesian to me. If people define the good for themselves, how do we reconcile competing goods? Who gets to manage the value trade offs?