Hello,

Welcome to Known Unknowns, a newsletter where prices have meaning and all is right with the world.

Another existential question

I've always believed that studying markets offers answers to many important questions. I suppose that's why I became an economist. Through markets, we not only gain insight into how the economy works but also into the big questions that face humanity. I wrote before about how private equity can help answer the existential question: if a non-market price falls in value, does it rattle markets? This week, I explore the ultra-contemporary art market to address another big question: What comes first, the chicken or the egg? Or do prices on goods that lack an objective value need manipulation to make the market function, or do the prices lack meaning because they’re manipulated from the start?

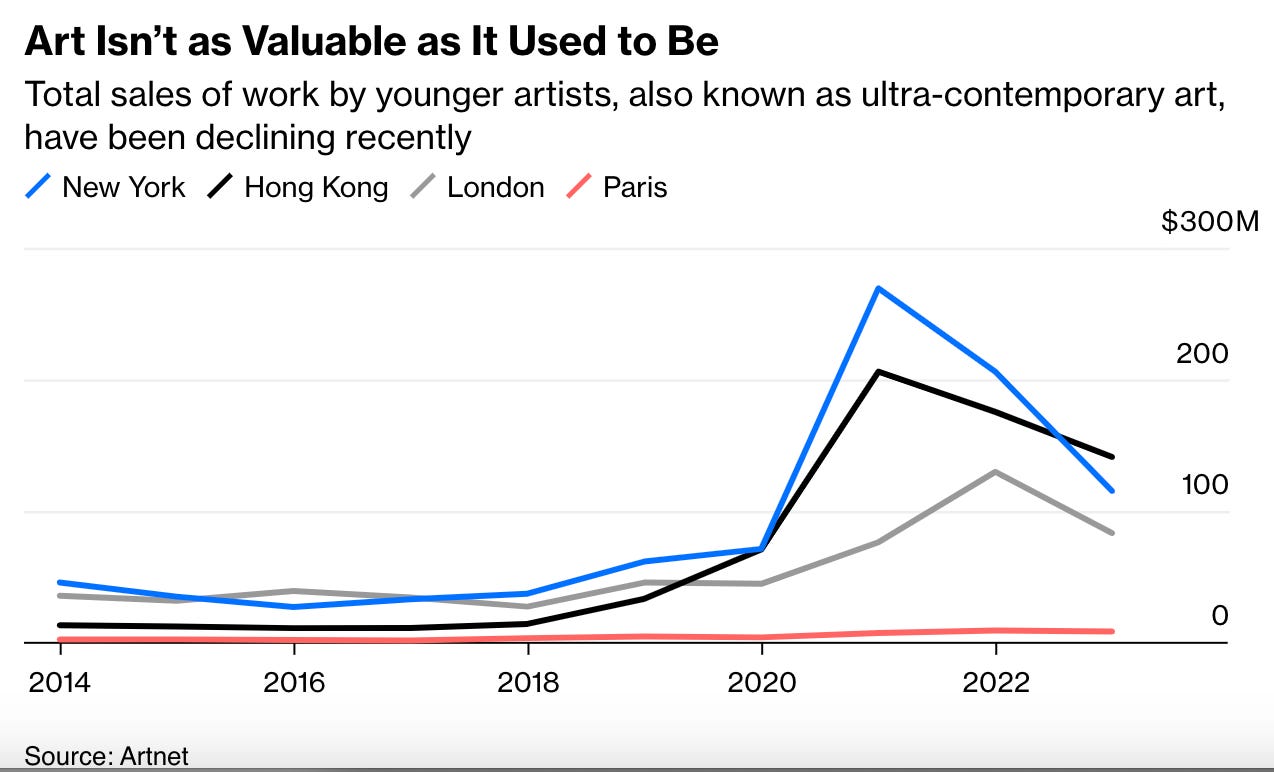

The market for ultra-contemporary art is imploding.

It’s perhaps the hardest segment of the art market to price, partly because art is always hard to value—especially for young, unproven artists. It doesn’t help that the primary art market (where most of their work is sold) is so heavily manipulated and opaque. A recent boom meant more work ended up at auction, prices were bid up, and now they’re falling. Unlike other markets, a falling price in art can be a kiss of death. Because value is so uncertain, it suggests an artist was overvalued all along, leading the market for their work to crash, perhaps permanently.

This situation seems to justify manipulation in the primary market. However, maybe a falling price is such a bad signal because the market is manipulated to begin with, so no one trusts the prices, making them fragile.

It strikes me as odd how people in the industry keep saying, “We can’t leave it to the market,” as if market forces are dirty or immoral and price-fixing serves a higher purpose. Yet this is often said by people with a financial stake. If you want to make money in a market, you need to live with the whims of market pricing, just like the rest of us.

Jay Powell’s Legacy

While we’re on the topic of price manipulation, I've been reflecting on Jay Powell’s legacy. It’s an important question because it provides insight into effective monetary policy and how it should be used going forward. The challenge with monetary policy is that the economy and financial markets are always evolving. Milton Friedman may have been right about many things, but those insights may be less useful in some respects today. We must continue learning and adapting.

Now that a “soft landing” is upon us, it seems Powell has pulled off the impossible—reducing inflation with no harm to growth or the labor market. Maybe it’s luck, maybe it’s exceptional skill. I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt and allow him the credit. However, I believe he has much to answer for regarding the state of the housing market.

During the pandemic, mortgage rates reached record lows, largely due to the Fed’s interference—both buying up LOTS of mortgage backed securities and by keeping rates at zero, which encouraged banks to buy them as well. This drove spreads down to record lows. The Fed continued with their mega-QE and zero rates even as the housing market boomed (remember the bidding wars in Boise?) and for a full year after inflation returned, resulting in $8 trillion of mortgage originations.

Now, more than half of homeowners have mortgage rates below 4%, and many of them will never move, acting as a constraint on supply and creating a “weird” housing market for at least a decade.

The extra year of aggressive quantitative easing, which was way to big and continued for far too long, was hard to justify then and now, and it will have lasting effects. It stands out as one of the biggest monetary policy errors in recent memory.

Populism strikes back

I may be right in suspecting that Trump’s proposed tax exemptions are a step toward eliminating income taxes all-together and replacing them with a consumption tax—or rather, a consumption tax targeted at foreign-made goods. This approach would be quite regressive and increase the debt. Though do I like the idea of shifting to a consumption tax, but it is not how I would do it.

More concerning are the tariffs. They are they bad economics, but I’m unsure if Trump is even serious. I’m even more skeptical about the underlying desire to restore the manufacturing industry of the 1960s by making imported goods more expensive. Trying to revive the past is not the way to grow the economy. Manufacturing is over-romanticized; that 1960s economy was not as great as some remember, nor is it the future. If manufacturing is the future, it will likely be highly technical, employing fewer people, and not necessarily those with lower skills—-we can’t build our economy around it. For that reason the subsidies and industrial policy from the other side are just as problematic. Messing with prices only leads to a bigger mess.

That said, even as an ardent free-trade advocate, I feel challenged by the China situation. The beauty of a global economy is diversification and that makes us safer and richer. But it is all undermined if all our antibiotics are made in China. And if China is subsidizing its manufacturing to gain market share (and power), where does that leave free trade? I’m not sure what the answer is, but retaliatory protectionism is not it—it only makes everyone poorer.

Though at least Trump does have a coherent economic philosophy, even if I don’t agree with it.

Until next time, Pension Geeks!

Allison

I've always thought of art as consumption. The one time we sold a work of art because it had appreciated greatly in value (from a very low base) is something we regret. Because we liked the painting and now we miss it.

Is there really any chance of a coherent economic policy from either policy getting through the Congress ?