Photo by Austin Distel on Unsplash

Hello,

Welcome to Known Unknown—a newsletter that accepts the future is unpredictable. All you can do is observe the term premium, manage risk, and then hope and pray.

What to Look for in 2025

I suppose since everyone kept predicting a bear market over the past few years—and were wrong—the safe call is that 2025 will be a great year for stocks. Yet, we also get predictions interest rates will rise, inflation will return, and the Fed will shift away from “easing.” I’m not sure if that’s a consistent story. But who knows? These are strange times. I don’t know what will happen, and no one else does either. I recently wrote for Bloomberg about a few financial indicators that might help us make sense of things as they unfold.

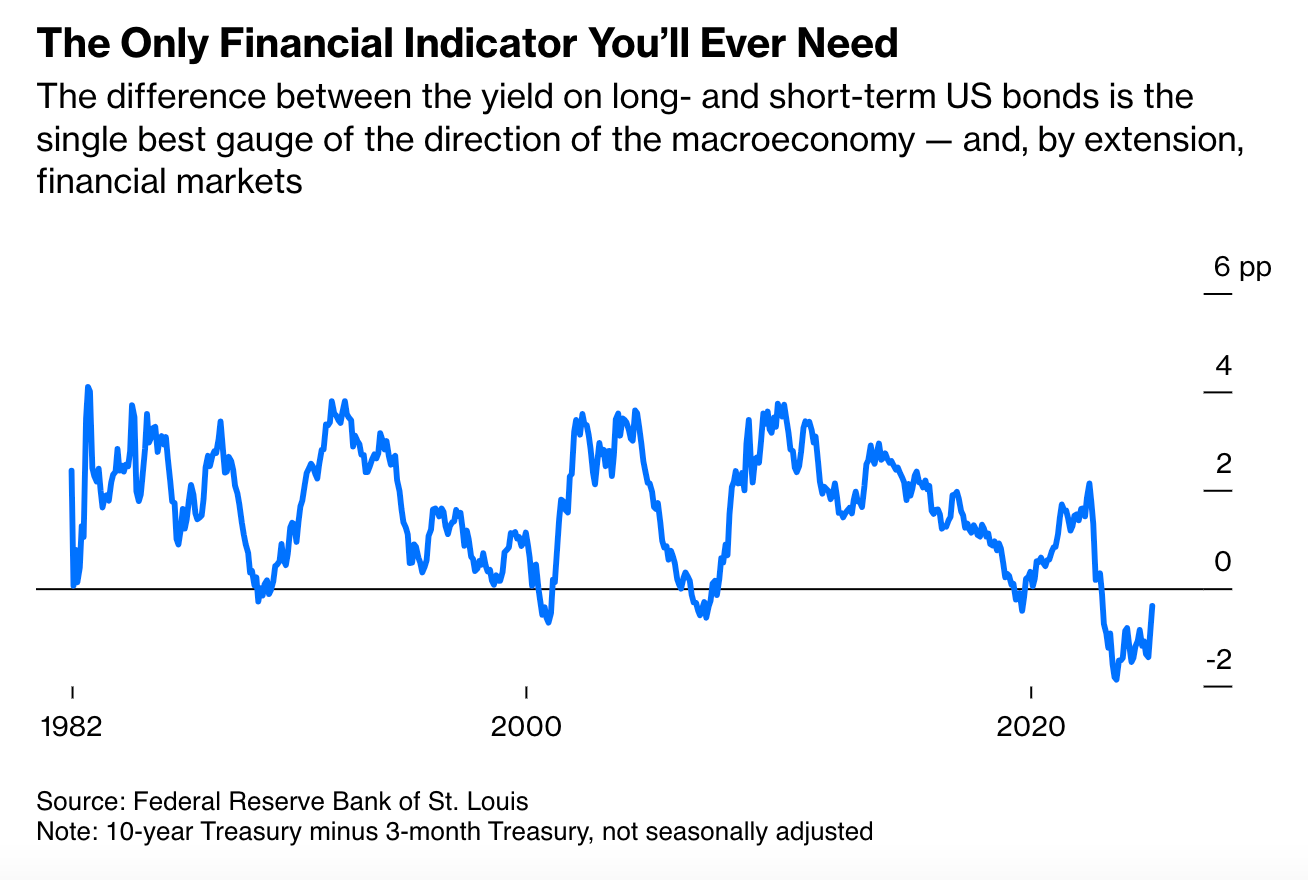

Generally, I expect the Trump economy to boost growth—though not enough to cover the cost of all the tax cuts and extensions. But between new innovation, deregulation, and lower corporate taxes, we can anticipate some growth. Inflation, however, may creep back up. All of this contributes to a bigger term premium. I am of the mind that the term premium is the most important of all macro/financial indicators. It reflects so much—the macro outlook, inflation expectations, inflation risk, and, of course, concerns about rising debt. This adds up to a larger term premium, higher 10-year yields, and consequently, higher mortgage rates for the foreseeable future.

Some people believe the Fed controls the entire yield curve. I’ve always thought those people were hopelessly naïve. Do they really believe in the expectations hypothesis? Such fools! But as I reflect on the past decade, I’m beginning to accept that when rates are near zero, the curve might be less segmented than in the past. There’s also evidence that large-scale QE lowered long-term yields.

Regardless, those days are over. Higher rates are back—up and down the curve—and the term premium tells us nearly everything we need to know. If it continues to increase, it suggests a higher growth and risk environment. Which, frankly, is how it should be.

Another indicator I considered including is capital inflows into private markets. Higher rates will likely deflate the sails of private equity and private credit. Leverage becomes more expensive, and private credit—laden with floating rate debt—is riskier than many realize. In a higher rate environment, institutional investors will crave less yield, making expensive fees and liquidity lock-ups less appealing. This shift will expose underperforming private investments.

Pension Geeks know I’m skeptical of this market. I do believe private markets are valuable—the returns were solid for a while for a reason. I for one am not offended by private equity ownership of many of our services. But I suspect the market has grown too large and is flush with more capital than makes sense. Public markets correct faster due to transparency. But nothing lasts forever, even if asset prices are made up, and the private market is due for a correction. If capital inflows into private markets dwindle this year, it may signal that the time is now.

Moving into a high-rate for longer environment will reveal where all the bodies are buried in financial markets. And no place is more opaque and full of skeletons than private markets. Maybe this is the year we find out what’s in there.

There’s No Good Debt or Bad Debt

One thing you we are taught in both public and personal finance is there is good and bad debt. Betting on the Super Bowl with a loan? Bad debt. Buying a reasonably priced home with a mortgage? Good debt.

This logic extends to government debt. The idea is that debt issued to invest in the economy—like infrastructure—pays for itself through growth. Republicans apply the same rationale to tax cuts.

The problem is, we live in an uncertain world. Good debt is defined by its payoff, but ex-ante, what will pay off is unclear. I wrote about one example: imagine it’s 2010, and you borrow $200,000 to either buy Bitcoin or fund an engineering degree at MIT. What qualifies as good debt? The realized payoff alone isn’t a sufficient metric.

As long as uncertainty exists, there’s no such thing as good or bad debt—only good or bad risk management. This means selecting prudent investments, managing their costs, carefully structuring financing (such as loan types and interest rate risk), hedging and insurance. It sounds obvious, but these considerations are often overlooked, particularly in public finance. We hear that any government spending will generate growth—even if it’s just digging and refilling holes. But rarely do we discuss the types of bonds to issue when borrowing. This is why we missed the opportunity to lock in low rates.

Perhaps this will be the year of risk management. But I’m not holding my breath. Andrew Biggs has a great op-ed in The New York Times about how it can all unravel—as it did in Chicago.

Oh, and so much for small-walled gardens. Who (besides everyone) saw that coming?

Happy New Year, Pension Geeks!

Allison

Yeah it's a strange sh-tshow...I can't even find a shred of tangibility to hang my hat on from either party, the stock market, or the Federal Reserve. So, I put money in high yield savings accounts and precious metals and keep the popcorn handy, lol.

Do you really think DOGE will deregulate anything? It seems to me they are exclusively focused on reducing expenditures, mainly transfers.

Aside from repealing the silly 15% minimum will there be any reduction in in business taxes?

Deficits? I expect higher. Trade more restricted. Immigration more limited (even if he does not deport settled immigrants). All this is anti-growth.