Photo by Liam McGarry on Unsplash

Hello,

Welcome to Known Unknowns, a newsletter where the economy is not zero-sum, but there are still trade-offs.

Why do people vote the way they do

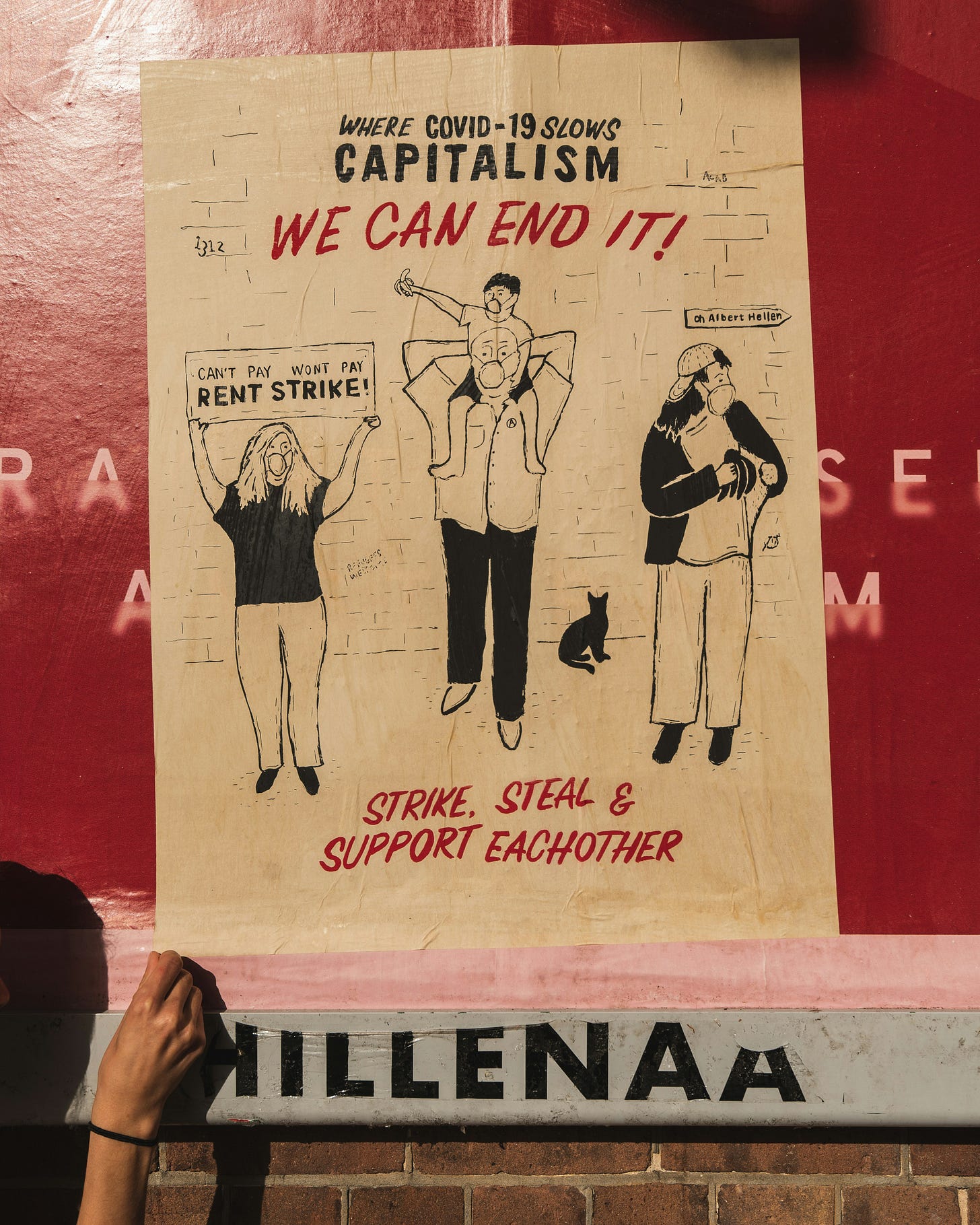

I might be losing it. I was at a party recently and found myself screaming at someone about rent control. “NO, it is not just a theory some economists have that it increases prices for everyone else!!!!”

I am never one to judge people’s choices, but this wholesale rejection of the most basic economic principles by some voters is driving me crazy. I turn to the data to calm myself. It seems much of the probable Mayor’s base is college-educated, high-ish earners who live in the bohemian parts of Brooklyn. If you look at their economic situation, there are reasons they feel resentful, and it’s important to understand what’s going on with them—because historically, a disappointed and entitled haute bourgeoisie causes all sorts of trouble.

It is more complicated than elite overproduction. Many of these people are elite; this is not just baristas with feminist studies degrees. I wrote for Bloomberg about the growing divide between the economic and cultural elite.

Many of these socialists who want fewer cops have cultural elite jobs: in media, the arts, non-profits, and the like. These jobs require living in a big, culturally dominant city. But these cities have gotten very expensive—too expensive to buy a home or raise a family, even if you earn a decent living. According to the data, I estimate that “creatives” in Brooklyn have median earnings of about $125,000, and only about 30% own a home. To make matters worse, they live alongside the people they grew up with and went to school with who “sold out.” The “sell-outs” work in law, consulting, or finance, make much more, and almost 60% own their homes. This may be why the new Marxists believe the economy is zero-sum; when it comes to buying a Brooklyn brownstone, it is.

It’s getting worse because a generation ago, cities were much cheaper. You could work in a non-profit or be a somewhat successful journalist and raise a family in the city. The returns to an economic elite job have also increased relative to the cultural elite. True, the culturally elite made their career choices—they could have worked in finance too. And they still earn more than most New Yorkers. But that’s not much comfort; affordability is a real problem.

But the tragedy is they are making choices that will make their problems worse. Either that, or the public safety issue will make the city more affordable—but not in a good way. Unfortunately, a nice smile does not overcome the basic laws of economics. Markets come for you eventually.

Spare me

I also wrote my thoughts on One Big Beautiful Bill. Pension Geeks know there is no bigger debt hawk than I. But for some reason, I can’t get that upset about OBBB. It is hardly what’s going to break the economy or our debt markets, considering all the other spending we are doing. And if you freak out about any cut to Medicaid—a program that has grown more than 50% in the last few years—I don’t take you seriously as a debt worrier.

Indulge me in a technical digression. Several years ago, some economists argued we could spend like crazy because real interest rates (r) were lower than economic growth (g). This always struck me as a batty argument because what matters here is not current r and g, but future r and g—since we are taking on a long-term liability. Unless you think current r and g tell you everything about future r and g—and if that’s true, you’re no better than an actuary!

Anyhow, it is equally silly to say now that r is bigger than g we can’t spend anymore—unless you think something changed with the long-term outlook for both variables. I suppose you could argue what’s changed is higher debt levels, but higher debt was always in our future, so that makes no sense either.

Look, I’d love to have serious tax reform that raises more revenue by broadening the base, and I’d love serious entitlement reform. But that wasn’t in the cards this time. We’ll need to take it on soon. And all these Johnny-come-lately debt hawks seem to be making political, not economic, arguments—and that’s not what we need if we want to have a serious conversation about the debt.

This time really is different

In that spirit, I am glad two Senators have floated one idea to fix Social Security: take on $26.1 trillion of debt and invest in the stock market. That’s a start. But what bothers me most about it is they think the market will perform so well (I calculate they need at least a consistent 5% real return—more if rates go up) that there needn’t be any tax increases or benefit cuts. That’s crazy. Why do so many people think the future value of random variables won’t change? But hey, I am all for diversifying how we finance Social Security, and they are getting the conversation started.

But we need to take risk management more seriously—especially when it comes to long-term liabilities. I wrote for Bloomberg about three big macro trends that are about to change investing:

Higher rates

AI changes in productivity

Global fragmentation

They will all increase risk, though also expected return. For the last 20 years any fool could make money in markets. But that won’t be true anymore. Risk management will matter, so maybe now is not the time to take a $26 trillion risky leveraged bet.

But what can you expect? The online version of my last City Journal article is up. It explains how low rates created an environment where politicians and CEOs all thought there were no trade-offs—just free lunches everywhere they looked. Now rates are higher (and may go higher still), but they have not changed their behavior. How does that end?

In other news

I had an exceptionally fun time on the new Businessweek podcast. I explained how the US economy is like a middle-aged man with a belly. He’s still very productive and has some good years ahead, but the extra weight he’s carrying is slowing him down and will eventually cause some problems.

Until next time, Pension Geeks!

Allison

Anyone who thought and still thinks that r less than g, however an optimistic they may be in forecasting these variables has zero real world experience in dealing with excessive debt of corporate enterprises, or over levered assets. Simply put: You cannot earn your way in to a bad balance sheet.

And as to overall US debt it does not need to be repaid as many pundits seem to say; but fixed income investors need to see it its path will not be increasing at the current rate, indefinitely ; a good start would be to move towards a balanced fiscal budget even if takes several years to get there and enact microeconomic policies that will allow for some real growth.

For now all the Fed Gov seems to be is an institution that doles out dollars for entitlements( SS and healthcare) and service interest on old debt. Americans want their entitlements, but also want low taxes or not to have to pay more in taxes to get the benefits. So, Pols will accommodate them, at least for now.

"Like a middle-aged man with a belly"

Have we met?